40 Years of Pride Toronto – Looking Back and Looking Ahead

This month we invited two talented guest writers to share their thoughts on the 40th Anniversary of Pride Toronto, and to think about where Pride will be in another 40 years. Karibu Ramos is a self-described fat disabled queer who is the founder and Executive Director at Elevate Equity. Brad Fraser is an award winning writer/director/host who has worked extensively in various media including plays, film and television. We are very excited to share their words with you as we celebrate 40 magical years of Toronto Pride. Please read below to see what they envision for the future of Pride!

*Banner image of Black Lives Matter Toronto at Toronto Pride on June 25, 2017. Photo Credit: Nick Lachance/Xtra

Karibu Ramos’s Vision for Pride:

“As we approach the 40th anniversary of Pride in the GTA, there’s a hint of dissatisfaction for all the history that surrounds 2SLGBTQ+ communities in 2021: Whose histories do we recount? Whose history wasn’t recorded? Whose history was recorded and destroyed? Since 1970 the moments of inconsolable grief grew into sacred rage and grew into an action of indignation through activism. By 1980 activism and advocacy turned to celebration, society’s “progression” recognized capitalistic opportunity, until finally, a celebration of the Pink Dollar promises to hold us intrigued every June.

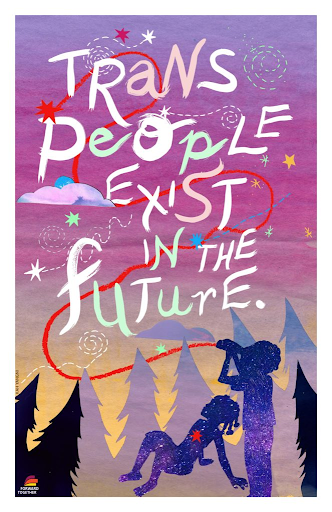

Artwork by Kah Yangni (@kahyangni on Instagram www.kahyangni.com) and Forward Together (@fwdtogether).

We wear our fishnet bodysuits, paint smoked out rainbows on our eyelids, and drink bottomless mimosas every year. We convince ourselves that a celebration is in order, arms linked with chosen family, we watch the many emerging queer films, we run into our exes, we kiss our friends on the mouth, we look at each other and dance. We look at each other, and we forget why we’re stumbling home at 4am. We bask inside of Gemini season’s curiosity and interweave each other’s daily grievances with transphobia and queerphobia for a month that says, “We see you, we value you, we’ll pay you. Dance it all away!”

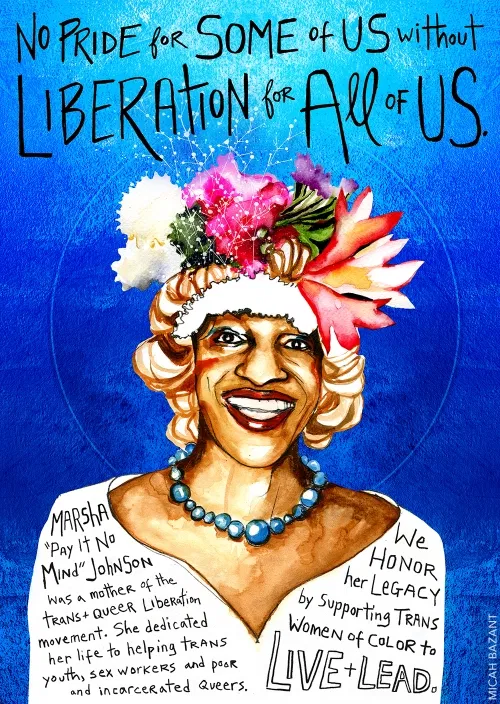

This year, the calendar notifications pile up in our inboxes of the many online events we registered for in advance, we find ourselves time and time again whether in our living room (or dreaming of being on a patio) perplexed and swinging between grief, rage, and celebration. After all, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Riviera put their bodies at the crucifix of violence so that in 2021 we could host virtual Pride events.

And so I find myself here today, somewhere in between grief, rage, celebration and actioning indignation. Those of us who have been walking a tightrope of rigidity on whether or not Pride has lost its meaning (long before the pandemic) continue to face the echoes of, “how will you show up?” We sit with the humbling reality that we have every opportunity to ditch our value systems and allow police to march with us during Pride parades. The same police state that enacted and continues to enact horrific violence towards our community. Every year we are given an option to partake in some well-deserved joy, every year we are gifted with the choice to honour Black and brown Trans femmes who gave us the option to choose in the first place. I would be remiss not to name this, I would be lying if I said I’ve done so every year since I came out at 15.

As a fat disabled queer and trans nonbinary person of the diaspora – I daydream about those wide eyed, fake lash drooping, dramatic acrylics, and fading black matte lipstick. The hands that would reach out to me no matter how sweaty, how fat, how recluse. I think about the neon teeth in the middle of the dance floor, bald heads, long legs, the wide hearts of the people that claimed me, the people I claimed in return. Pride has always been an exclusive experience only for the thin, white, able-bodied queers. The select times that I felt empowered enough to partake in some celebratory debauchery (with proud rolls exposed for days) I was only ever able to do so with Black and brown women and femmes.

So this year, like most years since coming out I sit with the questions more than the extra gigs or queer art that emerges in June. What about those of us who have always been on the sidelines of community? Those of us that are not the right kind of disabled, the right kind of mentally ill, the right kind of “messy”?

I reflect on the countless femmes who were not protected to make it to their next Pride.

Artwork by Kah Yangni (@kahyangni on Instagram www.kahyangni.com) and Forward Together (@fwdtogether).

For someone who considers themselves to be in the “thick of it” when it comes to actioning a new future for Trans and Nonbinary communities, this Pride I choose to celebrate the trans and nonbinary future ancestors making history they cannot destroy. I choose to look at all the brilliant trans people in and out of my life that reclaim themselves and each other on the daily. I celebrate the exchange in expressions when we see each other on a hot day, the days when our bodies are exposed to the classifying of cis people’s perception of gender. I see the way you nod with a crooked smile, part of me wants to believe you know I’m too fat and it’s too hot to wear a binder. A part of me wants to believe you don’t care and still see me. This pride I think about chosen family, those of us that share a similar notion to appreciating the anonymity of wearing a mask. Let me be explicit by saying that a metaphorical mask is worn on the daily regardless of COVID, whereas the masks everyone is required to wear has given us an added layer of protection. And yet, all of us clock each other with a silent admiration I can only describe as unflinching care, protection, and understanding.

During Pride’s 40th Anniversary, I am celebrating Black and brown Trans community. I am celebrating those of us who have been discarded for not having PhD level social justice verbiage, I am celebrating those of us who struggle to grasp queer culture in its entirety. The neurodiverse, the beautifully complex, nuanced queers that don’t subscribe to pronouns or gender. I celebrate our elders, those that have held these questions for centuries. I choose to celebrate the folks that call each other when their mental health settles enough to ‘check-in’ with our collective “Have you been taking care?”. I choose to celebrate the folks that see each other outside of being ‘queer famous’ and the activists that keep us in a constant state of transformation and collective action.

Mostly, I celebrate those of us sitting with the complexities of Pride and choosing to love one another to live to see another Pride month.”

About the Writer:

Karibu Ramos is a self-described fat disabled queer. They are the founder and Executive Director at Elevate Equity – Toronto’s first trans-led organization promoting employment and entrepreneurship access for racialized Trans community. Karibu’s experience working with Trans and Nonbinary people in Canada and the US has greatly influenced the trajectory of their life’s purpose. Karibu is a strong believer in movement building, requiring multiple approaches towards liberation. They choose to focus their efforts on financial self-sustainability for Trans people in the GTA. Karibu grew up in El Salvador and is now a settler on unceded Algonquin territory where you will find them tending to their plant children, embracing shadow work, and writing, with a heart full of so much hope.

Karibu Ramos is a self-described fat disabled queer. They are the founder and Executive Director at Elevate Equity – Toronto’s first trans-led organization promoting employment and entrepreneurship access for racialized Trans community. Karibu’s experience working with Trans and Nonbinary people in Canada and the US has greatly influenced the trajectory of their life’s purpose. Karibu is a strong believer in movement building, requiring multiple approaches towards liberation. They choose to focus their efforts on financial self-sustainability for Trans people in the GTA. Karibu grew up in El Salvador and is now a settler on unceded Algonquin territory where you will find them tending to their plant children, embracing shadow work, and writing, with a heart full of so much hope.

Website | Instagram | Facebook

Brad Fraser’s Vision for Pride: LET’S MARCH THIS SHIT BACKWARD

“I’ve seen a great many Pride celebrations.

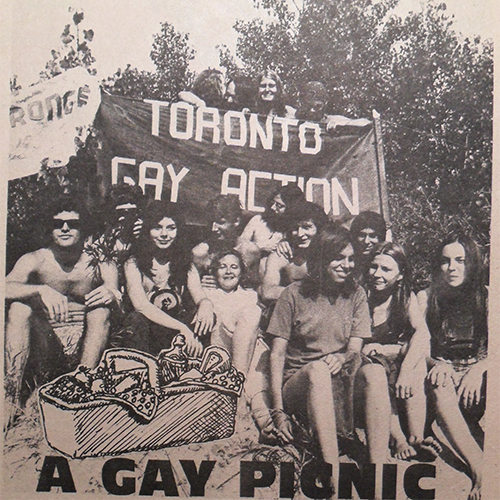

I remember when they were picnics held in city parks and on the Toronto islands. Those gatherings quickly became marches through prominent parts of various large cities as we demanded visibility, acknowledgement and the redress of historical wrongs. It wasn’t a parade yet, it was a march of defiance that said “We are here, we are queer and we’re not going anywhere.”

The first of these marches came out of New York and San Francisco, with their sizeable queer populations, and were illegal acts designed to stop traffic and register legitimate protest, but they quickly spread to smaller centers.

The march, and the inevitable party that followed, grew larger every year as more people found the courage to take part. Groups began to differentiate themselves; Dykes on Bikes, Totally Naked Toronto Men, the wonderful supportive parents and families who are PFLAG, the clogging club, Lesbian Mothers, The Judy Garland Memorial Bowling League, and various others made themselves known through their shared interests and issues.

In these early marches some men were naked and some women bared their breasts in a display of defiance. We were tired of the world telling us we were mentally ill just for being who we were. We flaunted our bodies, our beliefs, refusing to be shut down by the straight world that viewed these early celebrations with derision and hostility. Their disapproval would not stop us from having a good time or being our powerful selves.

Often religious groups and homophobes would show up to voice their hatred, and promptly found themselves shouted down, or surrounded by mobs of unruly queers who would laugh in their faces, empowered by finally being in a situation where we, not they, were the majority.

And then we were hit by the AIDS crisis. Gay Pride, as it was known, took on a new importance. We were now fighting for our lives. The few hundred who had partaken of Gay Pride previously became thousands as we lined Yonge Street. The march was now a parade complete with floats, marching bands, and even more participants. In those years there were no barriers between the parade and the spectators, many of whom would join the end of the parade, further eliminating any differentiation between those who marched and those who cheered. We all mingled into a river of community.

Pride became a sort of family reunion where you were guaranteed to run into the same people every year and catch up on what had happened since the last Pride celebration. What we were doing was none of the straight world’s business. If we weren’t given the same rights and freedoms they had then what obligation did we have to follow their rules? Our hedonism was political and our politics on Pride Day were about love and acceptance of one another, whatever subgroup we might fall into. We mourned our dead, cared for our sick, and refused to be beaten down.

Alley Yapput, Stacy Status, and June Thunderchild at Pride, Unknown photographer, 1992, Toronto, Ontario, Courtesy of the University of Winnipeg Archives, Two-Spirited Collection (17.026)

Eventually our straight allies joined the fun and we welcomed them to our party with open arms. Businesses began to look at Pride Day and see dollar signs in this horde of outsiders, many of whom had great power as consumers.

That’s when the corporate sponsorships started.

What had been a single-day celebration officially took over the closest weekend. Barriers were erected to separate the parade from the audience. Larger numbers of straight people showed up every year as word of the crazy partying and intense fellowship spread. Prices at local bars and restaurants went up just for Pride Day. The number of attendees began rise at an exhilarating, and then alarming, rate.

The board that governed Pride grew and an event that had reveled in diversity was now asked to prove its commitment to diversity. The community began to fragment as one sub-group demanded recognition independent of the larger group. Pride Day became Pride Week to ensure further monetization of the concept. Political factions accused one another of racism and repression. The corporate media weaponized free speech and reasoned dissent stoking political strife within the community. Justifiable issues concerning race, class and gender inclusivity that should’ve been discussions became pitched battles; everything concerning Pride seemed to culminate in accusations of abuse, corruption and, looking at their corporately sponsored financial history, bureaucratic incompetence.

Pride scraped rock bottom the year Black Lives Matter protesters stopped the parade to call attention to the disproportionate number of sanctioned deaths experienced by people of colour every year and Pride Toronto, and much of the community, didn’t unquestioningly support their protest. A movement that had once illegally disrupted traffic in order to draw attention to the mistreatment and disproportionate number of sanctioned deaths experienced by gay people was incensed that a more repressed group of people would rudely disrupt their now meaningless orgy of corporatism, consumerism, assimilation and fake Liberalism. After that Pride was all stoned kids, bi-curious married couples, and drunken straight girls peeing in the street.

This pandemic which has suspended us in merciless ether that renders us immobile but in no way stops the aging process, have given Pride, and all of us, an opportunity to rethink and reset.

We are a diverse community. Whatever label or string of meaningless letters we use to define ourselves, we are, universally, people who believe everyone must have equal rights and status in our society regardless of any differences. If this is not the essence of our battle then what do we have to be proud of? Demanding rights and privileges for yourself while rejecting that same opportunity for others is not something that should instill Pride.

If you don’t have to be gay or lesbian to be queer anymore then sexual signifiers mean little, so why they are even attached to Pride? We are not just marching for queer people, we are marching for every minority that is discriminated against by the majority anywhere in the world. We are marching for a true democracy, a world where no one is demeaned for being who they are, and everyone has the same opportunities as everyone else.

When we think that way, whatever sex, gender, race, religion or creed we are, we are no longer minorities, we are an army united in a common cause. And we can change the world so it works for everyone, not just the chosen few. We must let go of our demand for individual recognition and allow that recognition to happen in our acceptance of our unique place within the larger community.

We don’t need a week long orgy of alcohol, drugs and consumerism to make this happen. We don’t need a week of small parades for every sub-group within the larger group. We don’t need government grants or corporate sponsorship. All we need is one large, unified parade that makes our numbers clear and our demands unassailable. We need to look back at our history to understand why this celebration started and reconnect with the anger that helped us to change so much.

That’s the future I’d like to see.”

About the Writer:

Brad Fraser is an award winning writer/director/host who has worked extensively in various media. Credits include plays; Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love, Poor Super Man, True Love Lies, Kill Me Now, and others produced worldwide, film; Love and Human Remains, writer and Leaving Metropolis, writer director, and television; Queer as Folk, writer, story editor and associate producer and Jawbreaker which he hosted for two seasons on Out TV. He has written a number of projects for radio, CBC and BBC, as well as regular columns and stories for Xtra, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star and others. He has been the recipient of a number of prestigious awards, twice listed in Tim Magazine’s Top Ten Plays of the year, and has recently finished his Masters’ degree in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Toronto. Brad’s play Kill Me Now was nominated for a Governor General’s Award in 2016 and is currently filming in South Korea as well as being in development for a film in Canada. His memoir “All the Rage” has just been released by Penguin/Random House.

Brad Fraser is an award winning writer/director/host who has worked extensively in various media. Credits include plays; Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love, Poor Super Man, True Love Lies, Kill Me Now, and others produced worldwide, film; Love and Human Remains, writer and Leaving Metropolis, writer director, and television; Queer as Folk, writer, story editor and associate producer and Jawbreaker which he hosted for two seasons on Out TV. He has written a number of projects for radio, CBC and BBC, as well as regular columns and stories for Xtra, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star and others. He has been the recipient of a number of prestigious awards, twice listed in Tim Magazine’s Top Ten Plays of the year, and has recently finished his Masters’ degree in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Toronto. Brad’s play Kill Me Now was nominated for a Governor General’s Award in 2016 and is currently filming in South Korea as well as being in development for a film in Canada. His memoir “All the Rage” has just been released by Penguin/Random House.